The Forgotten

Stories of World War One soldiers in unmarked graves

A Friends of Toowong Cemetery volunteer and ex-serviceman asked, "why are there so many unmarked graves in the soldier’s section?". Over 600 soldiers in unmarked graves have been discovered in Portion 10 of Toowong Cemetery. Approximately 13% of all soldiers buried at Toowong Cemetery are in unmarked graves.

On 19 February 2025, Friends of Toowong Cemetery received a grant to mark 42 graves with a cement plinth and plaque.

World War One

Australia’s losses from World War One were heavy for a nation of just 4.9 million. The combined total of all Australian armed forces sent overseas during the war was about 340,000. Around 213,000 members of the Australian Imperial Forces (A.I.F.) became battle casualties during the conflict:

- almost 54,000 died

- ~4,000 were taken prisoner

- ~155,000 were wounded.

While most recovered to rejoin their units or at least remain in service of one kind or another, a significant portion were not fit to continue.

Often the scars could not be seen and manifested themselves in a range of mental illnesses. Many soldiers committed suicide particularly soldiers that could not find work or were suffering greatly from physical or mental illnesses.

It was common for returning soldiers from all over Australia to be discharged in Queensland in order to convalesce in a warmer climate including in care institutions, mental institutions or hospitals such as:

- Dunwich Benevolent Asylum (encompassing the Inebriates Institute)

- Goodna Mental Asylum and others further out in smaller towns.

- Soldier’s settlement farms in places including Coominya and Beerburrum.

Why are there so many unmarked graves?

Many soldiers were destitute when they died. With no family in Queensland (or Australia as many came from Great Britain) there was no one to organise and pay for a headstone.

The 1924 Toowong Cemetery schedule of fees stated:

The lowest amount now accepted to enable a grave to be attended to in perpetuity is £50. [$5,000 in today’s terms]

These amounts are paid into a Trust Fund (over £1200 has been already received for this purpose) and a formal agreement is made between the Trustees and the relatives or parties who provide the money. The interest on this money is devoted solely to the purposes of the Trust, and in this way the Trustees are enabled to keep the enclosure perpetually in good order, attending to the monument, and stone coping and railings whenever necessary, and re-lettering and painting whenever desirable.

Gruesome detail

Some of these stories end with soldiers committing suicide. Details are hidden in boxes like this. You can click to open and read them if you chooose.

Use the Toowong Cemetery map to help you visit the graves in this story. Click the grave location (portion‑section‑grave) beside each person's name to view an aerial image of the grave.

John Frederick Inkson (10‑81‑16)

John Frederick Inkson was born in Victoria in 1895 to Annie Florence and William Garrard Inkson. John enlisted at age 21, an electrician by trade, but was a carpenter later in life. He served in 3rd and 10th Machine Gun Company. He was severely gassed according to his military records. After rejoining his unit, he was later admitted to hospital with influenza and bronchopneumonia.

John returned from the war and, like many soldiers, did not marry. He died aged 45 in 1940 at a boarding house in Upper Edward St. John's death was unusual based on conversations he had with police and the inquest into his death. A newspaper article stated:

Insert images and attribution from Word doc. Can't find exact articles on Trove

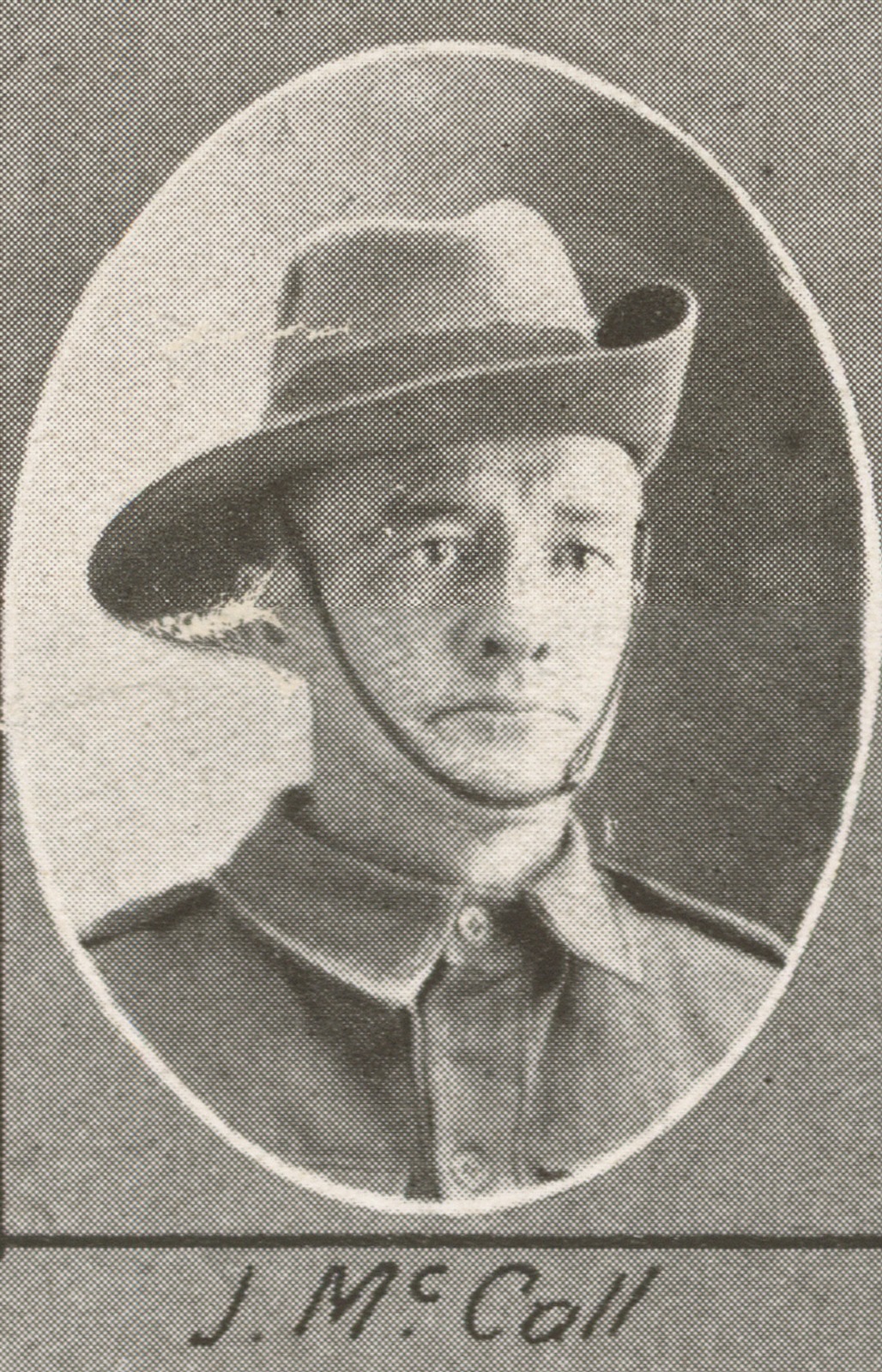

John McCall (10‑76‑23)

Born in 1878 in Sydney he worked as a labourer before enlisting at the age of 37 in Sydney. He embarked in October 1915 and a few years of fighting in France and Egypt and periods of illness, he was wounded in action with a gun shot wound to the right knee.

Since he returned in 1919 he had travelled Queensland extensively and ended up in Rockhampton. He then was admitted to Dunwich from February to March in 1939. Then a month before he died he came down from Rockhampton to Wynnum in August 1939 and lived at the presbytery. No relatives in Australia but sister in England. Sadly, John was hit and killed by a train one night at Wynnum. The headline in one of the newspapers said,

‘Train victim was war pensioner. McCall served with the 15th battalion AIF on Gallipoli and in France’.

A large newspaper article spoke about the dangers of that crossing but the driver said his train has 3 lights and it was said there is an electric light at the crossing. The article then said, 'the inquest was closed'.

You might think that’s the end of the story, until you read his medical file. John's lungs were found to be very congested and eodematous with universal pleural adhesions in both lungs plus laceration at based of left lung. So, it appears he was struggling with lung disease.

J. McCall, one of the soldiers photographed in The Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 1915 — State Library of Queensland.

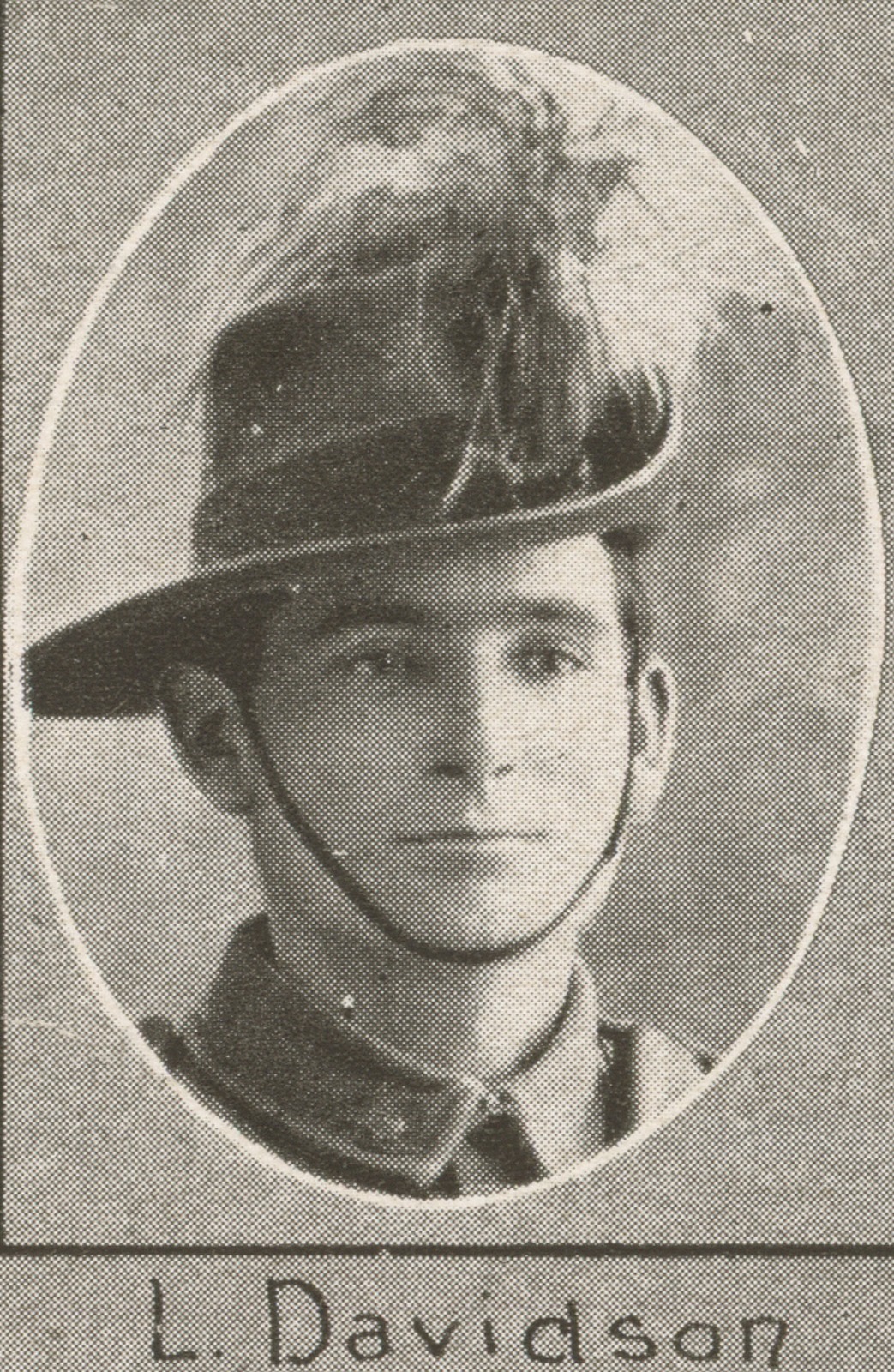

Lovatt Davidson (10‑78‑62)

Born in Scotland in 1874, Lovatt was 42 when he enrolled in the AIF in June 1916, his job listed as a Coachman. His service record says he embarked in October 1916, proceeded overseas to France and a few months later back to base classed as unfit. Soon after he left England to return to Australia as medially unfit with senility disability.

Insert image and attribution

Although discharged as unfit, and his medical file said he suffered from rheumatism during the war, he was denied a war pension after he was unable to continue his job as a cleaner due to ill health. He died possessing only a watch, chain and spectacles. In the Qld Museum memoirs they wrote that Lovatt described his health as,

“I hereby declare that my condition if anything is worse than at the time of my discharge. I suffer with palpitations, giddiness and shortness of breath. For some time past I have not been sleeping well and have gone off my food. My nerves are giving me considerable trouble and I am shaky, the least excitement knocking me over.”

After several months in the inebriation institution in Dunwich in 1925 he wrote,

“At night I am unable to sleep properly through pains in my body and my heart. I have to sit up very often to get my breath again. I also get very bad dreams of which I cannot explain the sensations. These dreams leave me very weak.”

Lovatt passed away on the 14th March 1938 with his death certificate recording the cause as a heart attack.

L. Davidson, one of the soldiers photographed in The Queenslander Pictorial, supplement to The Queenslander, 1915. — State Library of Queensland.

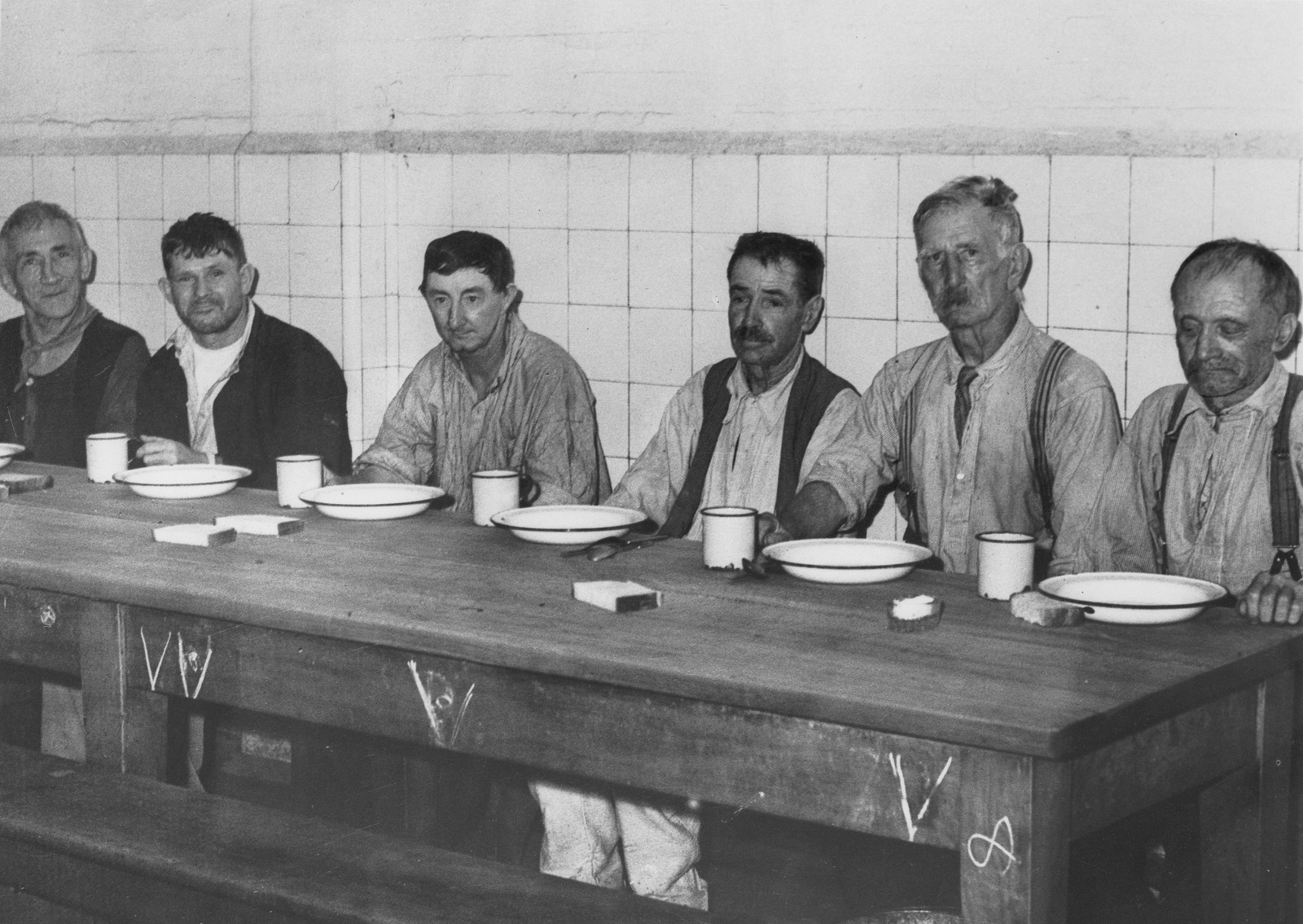

The Dunwich Benevolent Asylum

Many soldiers were sent to Dunwich on Stradbroke Island to convalesce or for treatment for alcoholism. Many died there.

The Asylum had been established in 1865 to house and care for people who were unable to provide for themselves – the poor and destitute, the disabled, diseased, the old and infirm, and in some cases, those with untreated mental illness. It was a major institution, with over 1,100 inmates at the turn of the century.

Within the Asylum, the Dunwich Inebriate Institution had been established to manage alcoholics. “Inebriates” found drunk on the streets of Brisbane and country towns could be sentenced by a magistrate to serve a period of time in Dunwich, to be “treated” for their condition, or people could refer themselves to the Institution voluntarily.

For a few years the Inebriate Institution had operated on Peel Island, but it was moved back to Dunwich just as men started returning from war. Over 450 men who had returned from fighting overseas spent time at Dunwich. At least 220 of these were admitted as “inebriates”.

Waiting for their meal at the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, North Stradbroke Island, 1938 — State Library of Queensland.

Tent town in Dunwich, Queensland, ca. 1928 — State Library of Queensland.

The Last Resort: the experience of First World War returned soldiers in the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum and the Dunwich Inebriate Institution, outlines how there was an outcry over the soldier’s treatment in Dunwich.

From as early as 1918, there was considerable public debate about the treatment of the returned servicemen at Dunwich, with concerns raised about the quality of the medical care, the standard of accommodation and the food. Advocates campaigned for soldiers to have access to an institution dedicated to their needs, noting that men who had made such sacrifices should be offered specialised care, not what was being offered at Dunwich. This letter to the editor reflected community concerns:

‘These men want to shake off the horrors of war, so we send them among the broken fragments of civilisation’

and

‘I feel, however, that the Returned Soldier who apparently owing to war service has become mentally deficient should not be placed with the ordinary lunatic, but should be in a ward or home where Returned Soldiers in a similar condition to himself only are housed'.

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum – Culture 11.

Is this text subject to copyright?

The Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia (RSSILA) in 1918 – found that the Inebriate Institution was not a suitable place for the returned servicemen, most of whom had entered voluntarily: It is alleged that it was represented to them that they were being sent to a place where the food and the facilities of Sport and Recreation would enable them to repair damage which has been done to their nervous system by the strain of active service. These men do not seem Inebriates in the ordinary sense of the term, but it is to be remembered that the shell shock and the experiences of men who have undergone a long spell of fighting brings their nervous system into such a state that a slight indulgence in Alcohol or any undue excitement or strain effects them immediately.

The RSSILA inquiry was widely reported in the popular press and led to a range of specific improvements to the conditions at Dunwich, including the introduction of Ward 9½ – a specific ward for returned soldiers. The soldiers were no longer required to work inside the Asylum, and the rations provided for them were slightly better and more plentiful. The Red Cross and other charities supplied cricket equipment, care packages and reading material for the men (Australian Red Cross Society 1915-1935). Unfortunately for the soldiers, the Medical Superintendent at the time, Dr. James Booth-Clarkson (figure 6), did not approve of these ‘privileges’. Booth-Clarkson had experienced a long military career including service in the Spanish-American War and the Boer War. He was of the opinion that alcoholism indicated a weakness in character, and thought the best treatment was sedation for several days, followed by a regime of abstinence and hard work. He resented what he saw as special treatment for the soldiers. He wrote in his Annual Report: ‘…in many cases there are readmissions, which is not to be wondered at when the surroundings are so comfortable and pleasant’ (Booth-Clarkson 1919). To discourage these soldiers enjoying the ‘luxuries’ of Dunwich, he advocated to the Repat that if a soldier was admitted to the Inebriate Institution more than twice, he should only be further committed to the Benevolent Asylum as an ordinary inmate, where there were expectations of work, fewer rations and a lower standard of accommodation

Bartholomew Thomas Sharkey (James Collins) (10‑52‑36)

Born in Ireland in 1874 Bartholomew Served in WWI under the name James Collins as he was too old to enlist at the time, being 40 years old. He enlisted in September 1914 stating he was 34. The age limit was initially 38 but as the war raged on it was increased to 45. Bart joined the 12th Battalion as a driver.

WWI details – extracts from file at National Archives of Australia website:

- 2.11.14 Embarked Freemantle for Alexandria

- 13.9.15 After ten months of fighting he went to hospital with a fractured pelvis in Alexandria (fall from horse)

- 28.1.16 He headed back to Australia 4 months later

- 18.7.16 Discharged

I was successful in finding a great nephew on Ancestry called Simon Gillespie who lives in America and who was very excited that he might finally be getting his grave marked. Bartholomew or Bart as Simon calls him, was quite ‘anxious to serve’ in the AIF. He received medals in the Boer War which he sent back to his nephews in Ireland. But he was quite unwell after the first world war and never fully recovered from his injury. He did not work after leaving the army – he travelled around Australia looking for work but was not successful. He had emphysema and cirrhosis of the liver and died from heart problems on 8th January 1941. An email from Simon is as follows but first a photo

Insert image and attribution

Walter Hammond (10‑51‑12)

When Walter enlisted at age 21 like a lot of soldiers listed a sibling as next of kin. Walter listed his sister Violet Hammond as his Next of Kin as both parents were deceased.

Walter’s war record shows he disembarked in April 1917 and by October 1917 he had lost an arm. He had to undergo the amputation when he was shot in the arm, foot and shoulder. He was right-handed so had to learn to write with his left. It’s interesting to note that WWI soldiers were not entitled to a full pension if they only had one amputation – they had to have had two amputations. He also suffered from chronic nephritis like a lot of soldiers – often due to little studied condition called ‘trench nephritis’.

His service record like many soldiers contained reference to some transgressions and the resulting penalties (forfeit of pay). Walter’s caught my eye as it was slightly unusual. During a concert at their dry canteen (no alcohol) Walter twice used insubordinate language in the presence of his officer. He had to forfeit three days’ pay for that.

Insert image and attribution

On his file are many letters from his sister Violet and responses from the Army – she was trying to find out his whereabouts, condition and requested if he could come home. Some extracts are as follows – Letter dated July 1918:

“To Senator Pearce

Dear sir,

your letter is to hand of July 15th re my brother Walter Hammond for which I thank you very sincerely. Can you tell me whether he is going duty or in the hospital, if so, would you kindly send me his address, as I would like to write direct to the hospital and surely someone would write a line to me for him. I keep writing every mail and still have not received a line since he was wounded in October 1917. I would very much rather know the worst than keep on trying to bear the suspense as it is killing me. I am very sorry to trouble you again but if I could only get the address where he is, I could write direct.

Thanking you in anticipation yours very gratefully

Violet Hammond.“

Violet even got a special inquiry officer appointed to her case to get her brother home or at least hear from him. This special officer wrote -

Insert image and attribution

Another letter from Violet said:

“Please pardon me for troubling you with a letter, but I am nearly distracted through worrying about my brother Walter Hammond who I was informed through the military was wounded 23rd October 1917 with gunshot wound in the right shoulder and was at the Eastbourne military hospital. It is now nearly 8 months and I have not heard one word from him and can get no information either at the Victoria Barracks Sydney nor the Red Cross as they said he enlisted in Queensland and I can only hear from them. As he is all I have belonging to me I would feel very grateful to you if you would let me know why he is not returned back to Australia as he cannot do any further service with his right arm off. Trusting you will do all in your power.

Anxiously yours Violet Hammond.“

Walter finally disembarked back in Australia in January 1919, presumably much to his sister’s delight, over a year after his gun shot wound which resulted in his amputation. But unfortunately, Walter died a few years later in 1922 at the age of 26, from tuberculosis. He is getting an official war grave.

Charles William Baldwin (10‑50‑31)

Born in England Charles was a 42-year-old painter when he enlisted in the 26th Battalion, a widower at the time with a daughter and son. Charles enlisted in 1915 and in his service record it states:

- 13/4/1916 Bronchitis

- 31/5/1916 Sick to hospital with bronchitis

- 1/6/1916 To hospital with synovitis in the knee

- 1/7/1916 admitted to hospital again with bronchitis and knee synovitis

- 1/5/1917 Went back to Australia with rheumatoid arthritis and discharged in Brisbane.

In April 1922 he was mentioned in the paper in an article titled “UNLICENSED HAWKER” where at the age of 53 he pleaded guilty to a charge that in Moorooka he carried on the business of a hawker and pedlar without a licence and was fined 3 pound in default seven days in prison.

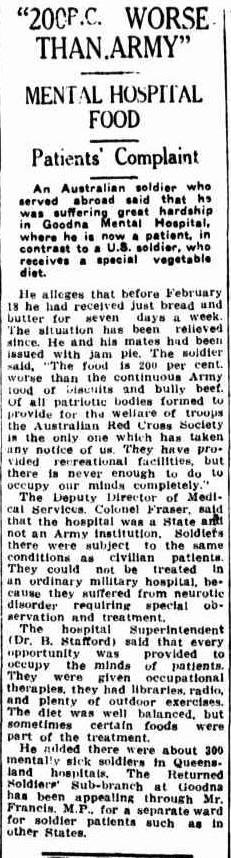

Charles somehow ended up in the Goodna mental hospital where he died in 1926 of ‘paralytic dementia’.

The Goodna Mental Asylum

The asylum at Goodna has had several names, firstly the Woogaroo Lunatic Asylum then Goodna Asylum for the Insane, Brisbane Special Hospital and Wolston Park Hospital. According to Wikipedia, by January 1942, 110 returned soldiers were inmates of Goodna Mental Hospital and the Australian Government expressed concern about the growing numbers being admitted. War veterans had become a significant minority of the hospital population since the final years of the First World War and Ellerton had decided upon consideration, that using existing institutions was preferable to building new facilities.

Can't use The Sandy Gallop Asylum image due to copyright. Consider this instead

In 1923 the bad food at Goodna mental asylum made the newspapers where the headline was, “200% worse than army food”.

"200P.C. WORSE THAN ARMY" (1943, February 22). Queensland Times (Ipswich, Qld. : 1909 - 1954), p. 3 (DAILY). Retrieved March 7, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article113999383

Thomas John Mullen (10‑50‑39)

Born in Bundaberg and enlisted age 25 and fought in the 26th infantry battalion. Thomas married after returning from war but no children, presumably because he caught mumps soon after arriving in England in October 1916. Fought in France and Belgium. Had bronchitis, dental issues and trench fever. He was wounded in action (gassed) in November 1916. Then in Belgium he had a gun shot wound (GSW) to an eye and ear. Later he was admitted to hospital for gas poisoning after being gassed again and with shell shock then dangerously ill with influenza. Finally returned to Australia in April 1919. It was written on his discharged papers that he had ‘nil incapacity’ although he did get a pension from 1922 onwards but died a year later. He lived in Bundaberg and when he became ill moved to Rosemount Hospital in Brisbane.

He died aged 33 from tuberculosis in a care home called Ardoyne at Corinda where many soldiers with lung complaints died and his file said ‘the deceased had no relatives although a friend used to visit him occasionally”. No next of kin (unsure what happened to his wife), died suddenly, so no condolence letter to be sent to anyone.

Group portrait of the 26th Australian Infantry Battalion at Enoggera Military Training Camp, Brisbane, 1915 — State Library of Queensland.

Henry Frederick Manning (10‑50‑40)

Enlisted in August 1914 and assigned to the 1st battery (cannons) as a gunner then transferred to the 115th Howitzer battery. Later wounded in action in Gallipoli where he suffered GSW to cheek and later promoted to bombardier and then to sergeant then sergeant major. Fought in France and was kicked by a horse which damaged his face again. Appointed second lieutenant in 1919. Gassed during the war.

Returned to Australia in March 1919.

Had ongoing medical issues after the war due to his gun shot wound to the face and being gassed and was awarded 25% pension. Suffered also from tuberculosis. Was on the Victoria Barracks Instruction Staff when he was retrenched. Henry died aged 36 when hit by a train at Auchenflower with his death certificate saying he died by being hit by a train. Newspaper report said:

RETURNED SOLDIER'S DEATH. (1923, February 21). Daily Examiner (Grafton, NSW : 1915 - 1954), p. 4. Retrieved March 7, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article195781692

Lord Sidney Horace Dutton (10‑34‑17)

Sidney enlisted age 21 in 1914 in Sydney where he lived with his father who was widowed prior to coming to Australia from England. He became acting sergeant. He was later appointed 2nd lieutenant in France and transferred to the 4th battalion. In 1917 it was written on his service record ‘The army cor commander wishes to express his appreciation of the gallant service rendered by Sidney Dutton during the recent operations.”

Sidney fought for the army for 5 long years before being discharged.

When Sidney Dutton returned home from the war, he was granted some farming land at Beerburrum similar to other soldiers as part of a resettlement program. The problem was a lot of soldiers had no experience farming plus the small allotments they were given often could not support any viable crop. Sidney came to Brisbane on and off looking for work but he was unable to find work. He died aged 31, in 1924, by suicide in Lang Park. The Trove articles about his death said as follows -

OUT OF WORK. WORRIED MAN'S SUICIDE.

In, the Inquiry Court yesterday afternoon, Mr, J, Burrows, J.P., ' continued the inquiry into the circumstances of the death of Sidney Dutton, whose dead body was found in Lang Park, with a bullet through his heart. John Hugh Langdon; at present residing at Burleigh Heads, gave evidence to the effect that he saw deceased in Queen Street, opposite the "Telegraph" Newspaper Company, about -4.30 p.m. the afternoon prior to his death. Deceased appeared to be worried about being out of work.

Constable William Henry Ridgway stated that he made Inquiries regarding the deceased, and found deceased owned a 32. calibre rifle, while at the Anzac Club. Witness could not get any trace of the rifle from them until it was found alongside deceased in Lang Park. It was possible to dismantle the rifle and wrap it up in paper, and carry it about without being seen. Possibly deceased did this. Witness was of opinion that deceased took his own life. Witness had been unable to get any information of anyone owing deceased any money. Harry Boyd Cuton, manager of the New Motor-car Coy., residing at Auchenflower, stated time he was acquainted with deceased for some years, and he always called at witness's home when he came in from Beerburrum. Witness often saw him at his office. The day before his death deceased called at about 5 p.m., and in the course of conversation deceased stated that he was out of work. Witness informed him there was always a home and three meals a day for him at his place. He left witness about 10.15 p.m., and said "Cheer, oh! I will see you again”. Witness went in direction of George Street. The parcel deceased was carrying did not appear to be a rifle. Witness knows of no one who owed deceased money, in fact, witness did not think deceased owned £5 for the last nine months. If he had lent anyone money it must have been previous to that. Deceased owned a block of land at Bulimba, and 10 shares in the Beerburrum Co-operative Coy. Witness made all arrangements for the burial of deceased. The inquiry was closed.”

Another Trove article titled “A debtor who waved him on” said that a witness said that Dutton told him there was a man that owed him 5 pounds but would not pay him. A lady who owned a boarding house in Red Hill said Dutton came to live in her boarding house a couple of months earlier. She said Dutton had a lively disposition.

Gruesome details

Content some people may not want to read.

Joseph Slack (10‑39‑2)

Joseph enlisted aged 44 in October in 1914 and was a Corporal in the 15th Battalion, awarded the Military Medal. His service record includes the following:

- 20.5.1915 Wounded in action in Gallipoli

- 14.8.1915 GSW left shoulder

- 16.8.1915 Wounded in action again, GSW right arm, admitted to hospital

- 19.9.1915 Admitted to hospital

- 24.10.1915 Admitted to hospital with dysentery

- 25.10.1915 Quinine poisoning following treatment for malaria, general debility

- 30.10.1915 Dysentery, admitted hospital

- 11.1.1916 Dysentery

- 1.2.1916 GSW serious, admitted hospital

- 2.3.1916 GSW thorax, invalided to Australia

His file states his pension was reduced in 1918 from £2 to £1 per fortnight.

Insert image and attribution

Gruesome details

On the 1st March 1919 Joseph was robbed of £17 by 3 men who went to court for their crimes. Then on 23rd March 1919, a little over 3 weeks later, Joseph died by suicide after drinking poison.

SUPPOSED POISONING (1919, March 24). Daily Standard (Brisbane, Qld. : 1912 - 1936), p. 6 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved March 7, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article179827445

As he is considered to have died ‘on service’ (i.e. he died before 31 March 1921) he will be awarded an official war grave.

Insert image and attribution

William Goldsmith (10‑84‑22)

Born in England William worked as a labourer prior to enlisting. A sapper in the tunnellers, William joined aged 31 in Feb 1917 and he was married with 3 children.

He fought for almost a year before being discharged in early 1918 due to hernia.

William died by drinking Lysol poison in 1942 at the age of 58. Now will get an official war grave as his death was recently deemed to be due to his war service.

I will read some extracts from an email I got from his great granddaughter.

SLEPT WITH AXE BESIDE HIS BED (1942, August 4). The Telegraph (Brisbane, Qld. : 1872 - 1947), p. 4 (CITY FINAL LAST MINUTE NEWS). Retrieved March 7, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article172605836

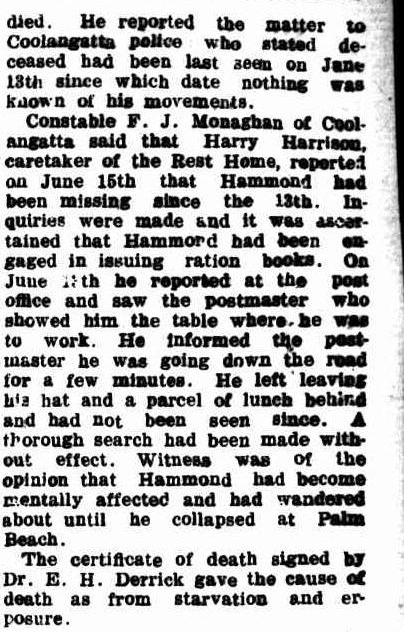

John Hartwell Hammond (10‑83‑4)

A plumber and a seaman before the war, John was born in Canada, enlisted in 1915 at the age of 44 and served in the 6th field company engineers. At the time he listed as next of kin a step sister in China and his father was deceased.

WWI details:

- 30/3/17 Admitted to hospital dental and mumps

- 19/5/18 Wounded in action - gun shot wound arms and left leg

- 18/9/18 to Furlough

- 15/2/19 Discharged with a disability due to multiple gun shot wounds

Was wounded in 22 places with fracture of left fibular and right hallux. Counter drains in both left and right feet and latn. Sequestrectomy (removal of dead portions of bone) in left foot. All wounds healed but feet tender to walk on and fore and middle finger of left hand are very weak and anaesthetic.

Lieutenant Colonel John Hammond received the distinguished conduct medal. He showed conspicuous gallantry.

TROVE ARTICLES BELOW

Sadly, John Died of starvation and exposure

DEATH INQUIRY (1942, November 18). South Coast Bulletin (Southport, Qld. : 1929 - 1954), p. 3. Retrieved March 7, 2025, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article188312545

Thomas Welsh (10‑68‑26)

Ensiled in Feb 1915 aged 38 and served in the 22nd Battalion. He was gassed in 1918 then went back into battle in France. Went home in late 1918 also suffering from rheumatism.

Welsh died aged 57 in 1933 from tuberculosis. Many soldiers caught tuberculosis at a young age and recovered before they served but were then gassed in the war which weakened their lungs and allowed the tuberculosis to reinfect them and they could not recover after that. Lung issues were the second leading cause of death in the first 100 soldiers I researched, close behind heart issues (refer to end of document for more info).

Many Australia soldiers died an early death after WWI due to their war service. Some soldiers were denied war pensions as their afflictions were deemed to be not from their war service but some soldiers died from those afflictions and have recently been allocated official war graves as their death is now deemed to be from their war service. For the returned Australian soldiers, more than 3,000 later died of tuberculosis and so many – with lungs irreversibly damaged by gas attacks – suffered severely from various respiratory infections that included not only tuberculosis but bronchitis, influenza, pneumonia etc

Back row, left to right: 818 Sergeant (Sgt) W. A. Freeman; 247 Lance Corporal (L/Cpl) T. Willis; 32 T. Welsh; 359 L/Cpl E. H. Davies; Lieutenant J. Kohn MC; 54 L. S. Benson; 460 S. Sharpe; 327 John Ash.

Middle row: 283 Corporal (Cpl) Robert Branton Wigger; 267 Cpl F. Vaughan; 161 J. Graham; 645 Bateman Missen; 659 R. Newman.

Front row: 205 Keith McRae; 19 Thomas Renehan; 979 J. Caffrey; 77 Company Quartermaster Sergeant James Cugley MSM; 832 Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant Reginald B. Hawkins MSM; 461 Sgt E. C. Smart.

Frederick Leslie Finney (10‑66‑3)

Frederick was an unmarried salesman who enlisted aged 30 in 1914 and was assigned to 1st general hospital, then 12th field ambulance then 2nd expeditionary.

Appointed sergeant, he caught influenza a few months after arriving. Frederick had an operation for varicose veins in Egypt then two attacks of gastritis then started suffering from rheumatism and had some stints in hospital with it but kept on going back out and fighting. He returned to Australian in late 1918 and discharged in May 1919.

Gruesome details

Frederick died by suicide at the age of 48 in 1932, killed by a train near Cabbage Tree Creek bridge. It says in the trove article that even though he had money he was a sick man and left behind a suicide letter.

Insert image and attribution

Frederick died at the age of 48 in 1932. He had no relatives in Australia, just some in England that he had been separated from for years.

There were two trove reports - Insert images and attribution

William Kalinovsky (10‑70A‑21)

Born in Russia, and a tailor by trade, he enlisted in the AIF September 1916 at the age of 23 and was in the 4th pioneers as a private and was transferred to the 12th battalion and fought in France. He was promoted to Lance Corporal in Dec 1918. He was later transferred to the 1st machine gun section.

William was classified as ‘no disability’ when assessed in 1920 upon return. He married and had a child as I found a great granddaughter on Ancestry who had visited his unmarked grave a long time ago with her father and she is thrilled that I am trying to get it marked.

From articles on Trove, it appeared that his business as a tailor went into financial difficulties and his wife left him taking the child. His medical file at National Australian Archives at Cannon Hill said his cause of death was hypertension and cardiac failure. Not long before he died, he started placing adverts in the newspaper to try to get more business.

Herbert John Haines (10‑70‑3)

Enlisted in 1915 in South Australia at age of 23. He was a tramway conductor before the war.

- Promoted to Lance Corporal in 1916 in the field in France

- Accidentally injured 7 days later

- Reporting missing in action in France in 11 November 1917, it was found he was a prisoner of war in Germany, released in January 1919. So, prisoner for year.

His Red Cross POW file included these articles:

Insert images and attribution

When he returned home, the repatriation department wrote to his previous employer trying to get him employed back on the trams. He worked there for around 12 months before he left.

He married in 1919 after coming back to Adelaide and had two children, one died as a baby. He was the support person for his mother. He was allocated a block of land in 1922. After marital problems he separated from his wife who wrote when she applied for a widow’s pension, which was knocked back,

“I was married to Herbert Haines in 1919 after his return from service and at that time he suffered from rheumatism. Immediately after our marriage he seemed very peculiar – would sit for long periods without speaking and avoided company. He would sometimes not converse with me for days.

About 1925 he began to wander away from home and was absent on occasions for about 3 weeks, at the end of which time he returned home and did not appear to know where he had been. From 1927 he did practically no work on the farm and in 1928 he gave it up and the farm was repossessed – he left me and I did not see him again.

Herbert ended up in Queensland and spent some time in Toowoomba. He developed mental problems and died penniless in prison from heart failure after he stole watch and got 2 months jail. Herbert died in 1934 from a heart attack at the age of 43.

Henry is getting an official war grave as he was a prisoner of war so it’s automatic.

The front page of the red cross files available on the internet are as follows

Insert images and attribution

Acknowledgements

Compiled and presented by Melissa Wren

Sources

- Returned Soldiers in the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum — State Library of Queensland